From mathematical informatics through graphic design to the renovation of a neo-Renaissance apartment building in the centre of Brno. He devotes all of his free time to architecture and has successfully renovated many apartments and houses. To make his own architectural ideas easy to implement, he developed Navigo3 software, which is now used by architectural and design offices at home and abroad. In an interview with Petr Humlíček.

How does a person who has studied mathematical computer science actually get a relationship with architecture?

You know, the initial decision to go into computer science came a bit from not knowing what I wanted to do. I was pretty good at math, computers were the rage in the 1990s, so I didn’t think much about anything else. But my interest in design was probably born in me before that. Around the time of the coup, my father – a physicist – was first allowed to go to Stuttgart for a year at the Max Planck Institute. It was a huge treat for my brother and I when he sent us a holiday card from there that was printed on a laser printer. There was nothing like it back then. I think it was made in TeX. I was blown away by it – it had a real font, not like when you write on a typewriter. It was a real smooth typeface and the way it was printed on the laser machine, it looked like a book. Then in college I accidentally bought a book about Ventura Publisher, written by Petr Koubský. I read that book in one breath. And then I got the Ventura installers from a college classmate. I solemnly installed it from floppy disks and for the first time I let some letters fall out of the floppy disks without any luck.

And have you ever used it in practice?

Of course it is! A friend brought me to the editorial office of Computer magazine. I thought I would write some articles, but the editorial staff was so small that the editors were planting the magazine themselves. And because I was very interested in it, I learned everything in a fortnight and was able to set the texts straight away. It also helped that I started taking some graphic design classes in college, so I started taking typography classes to understand fonts. Then, in my junior year of high school, I got the opportunity to start a magazine for money, so my partner and I started Omega Design. We had a vision that we would get money every month for this magazine, and that we would play with computers. In the end, we ended up getting much less than we originally thought, but I continued to have the urge and drive to try the graphics studio. I understood that this is what I want to do – simply creative things.

You said your dad was a physicist, you probably didn’t inherit this interest from him…

You’re right, I didn’t have much of an example at home – my dad, as a physicist, is a creative person, but in a different way, he doesn’t have much of a relationship with design. Mum might have loved to do it, but she never had the opportunity, she was a civil servant and she was also looking after the family. Rather, for me, it was a sum of all the occasions that somehow happily came together. The advantage was that computer graphics or computer processing in general was still a bit of a rarity in the 1990s, not everyone knew how to do it. Thanks to that, we were able to earn enough for a car in two months. That usually doesn’t happen anymore.

And the step from graphic design to architecture?

Parallel to my interest in graphic design, my relationship with architecture began to develop. Architect Jan Konečný helped me a lot. He used to come to Omega to make visualizations of the fair stands and houses he designed. Almost nobody did visualizations then either, and I started to learn from him. I picked up 3D studio relatively quickly, though of course naively.

I spent days and nights with Konecny because he had a very complicated time management. For example, he called in the morning saying he would be back in an hour, and he ended up coming three days later. And then he needed to do an overnight job. Thanks to him I started to perceive architecture a little differently. At first, I took it as many people do, who only look at the external effect, the impression of the facade. Gradually, however, I started to focus on the essence, on why things are done, how the floor plan works, what the proportions of the building are. At that time, we happened to be in a house from the 1930s, and Konečný explained to me that the window I was sitting at corresponded to it, and I began to see how great the house was. Later, I began to notice various details – for example, the travertine panelling around the stairs, which I had never noticed before. he didn’t notice. And I realized that it was actually all kind of good.

Where did it then break down to the practical implementation?

As we grew as a company, new premises were needed. Eventually we broke out of our studio apartment and into the basement, where the coal house used to be. It was a crazy space, we had the walls sandblasted to brick and because we were fans of all sorts of contraptions, we put in about thirty tons of iron. We made a floor that was made of pieces of sheet metal, instead of some there was glass and underneath there was a mirror, which turned the whole room upside down. We had about fifty variations of how we were going to do the table base. Then we thought of hanging the tables from the ceiling, which turned out to be a great idea, because nothing was hanging from below. The architects who saw it called it ironwork. It was actually the first industrial in Brno, for example Vaňkovka waited a few years after us.

As we grew as a company, new premises were needed. Eventually we broke out of our studio apartment and into the basement, where the coal house used to be. It was a crazy space, we had the walls sandblasted to brick and because we were fans of all sorts of contraptions, we put in about thirty tons of iron. We made a floor that was made of pieces of sheet metal, instead of some there was glass and underneath there was a mirror, which turned the whole room upside down. We had about fifty variations of how we were going to do the table base. Then we thought of hanging the tables from the ceiling, which turned out to be a great idea, because nothing was hanging from below. The architects who saw it called it ironwork. It was actually the first industrial in Brno, for example Vaňkovka waited a few years after us.

I wonder if you regretted not studying architecture…

I don’t look at it that way. I’ve been lucky to meet some great people. And also that I met my wife, who is very fond of architecture. She thought about studying it, but eventually realized that it was hard work and went into structural engineering and bridges. Her great-grandfather was the famous Vladimír Mareček, who saved the United Arts and Crafts Works from bankruptcy. And then also her father designs highways, so the relationship to architecture is huge in that family and what I needed was somewhere to learn.

You can’t help but notice the little Lego building behind you, what is it?

This is the kind of functionalist cottage in the Highlands that I dreamed of buying for ten years. Recently, I finally managed to buy it. The house is consumed, but without adverse intervention. So I’m doing a little visualization here. Lego has only one problem – it wasn’t designed for architectural construction, so it doesn’t have a good ratio of bricks to count. The models are a bit of a compromise, especially since I don’t want to make them big. This particular villa in the model looks a bit bigger and more spacious.

I suppose you can’t get away with just legos…

Absolutely not. I have a decent 3D imagination and I can tell myself what I want to be able to do, so I learned AutoCad fairly quickly because I was annoyed by always asking someone to redraw it for me. Of course I don’t have expert knowledge, I’m not an architect. But then again, I have time to play with it, to think about everything in all sorts of details, to change it to my complete satisfaction. Often it’s tiny adjustments, like the cottage I started drawing in my second year, so now I’m working out details like whether the sink will be five centimetres to the left or to the right in every room.

What was your first practical realization?

It came at a time when I was very happy to buy my first apartment on the top floor of a house from the 1930s. It was designed by the Jewish architect André Steiner. It was only a two-bedroom, but it had windows on three sides of the world, so even though it looked awful at first glance, with blue walls and terrible wallpaper, I knew it was a good base. When we sanded the parquet and painted the walls white, it was a shock. Over time, all the fine things that the apartment has became apparent. It wasn’t until my wife and I started to manage my brother’s apartment, which Dvořák was doing at the same time, that I began to realize the difference in the quality of the architectural design. Of course, by today’s standards, even these apartments are excellent. As time went on, I started to cultivate a finer skill set, getting opportunities to renovate friends’ apartments, sometimes on an unlimited budget, which allowed me to do the repairs really well.

What about this house on Charvatska Street?

We discovered it when we were looking for a new location for our growing company. It’s not a huge villa, of course, but it has its own charm and a beautiful history. The owner of the house was a fine man, Professor Jan Lenfeld, who was a legionary from the first war. He experienced the Baikal-Amur highway, where one soldier after another died as a result of poor hygiene. When he returned to Brno and built his career, he became the founder of Czechoslovak veterinary hygiene. He had many other activities and positions – he was a co-founder of the Sokol Královo Pole, founder of the first and still functioning Masonic Lodge. He died in his own bed on the floor below, just before the Gestapo came for him, making him the only one of his friends to avoid the concentration camp. When we bought it, the house looked ordinary, it was pretty run down, but it had an amazing staircase railing that won us over, original windows, doors and handles, and if a house has that, then everything is fine because something can be done about it without huge “conservation” costs.

With these apartments and buildings, we’re pretty much always revolving around functionalism…

That’s because I was most interested in them. The eclectic buildings used to seem too garish to me. Later I found out it was just lack of education. And then suddenly the opportunity arose to buy a neo-Renaissance tenement house, almost a palace, in Brno on Lidická Street. If someone had told me six months before that I would be fixing up a building like this, I would have laughed at them. But since I was already more experienced, I finally took the plunge on this big thing. Even though tens of millions of dollars were needed for the repairs, we got to work in stages. Today, I dare say that the interiors have been renovated beyond standard. I have every house I renovate sketched out in advance, including furniture and all the alternatives for future use. For example, on Lidická Street there may be a whole floor of offices or a combination of offices and flats, or even flats themselves. Everything counts.

If we’re talking about renovating a huge apartment building in the centre, how can we manage it all?

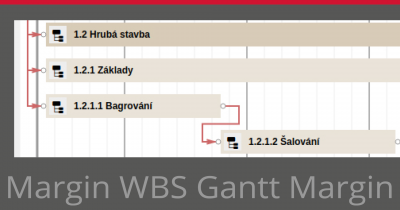

Over time, I realized that managing architectural projects is actually very similar to managing a graphic design firm. But in different dimensions. There is always a similar set of problems that everyone is solving. Everyone gets sometimes small, sometimes big orders, they can be well or badly sold, you don’t come out with money. Years ago, we started to create software for our own use to manage the company, because each of our orders was different and thus there was always a risk of financial loss. We called it Navigo3 and I soon found it great to use for managing my architectural projects. Over time, it somehow became popular and Navigo started to be rented from us by various architectural offices and design companies. Gradually, we have also created a specific and improved version just for them.

What is the specificity?

I’ve always tried to make Navigo have a good visual presentation, so I came up with graphical thermometers instead of tables with numbers. It turns out that this is what suits architects and designers very well, because they are very visual people. At Navigo, they can immediately see the state of their contract. Because my father-in-law and wife work for a company that is in the industry, we were able to discuss with them the principles that are important to projection. In addition, because construction has taken off in recent years and huge projects are being built, new complexes and neighbourhoods are being built, architects and designers are working in firms that often have dozens or even hundreds of people. And you can’t do that without a system.

The advantage is that we know and understand architectural practice, and today we have a number of architectural offices in our portfolio. That’s why architects don’t have to explain to us the elementary things they need in the software. For example, they do studies, documentation for zoning decisions and implementation documentation, because we simply know all this. We know what the typical size of their jobs are, how they should be structured, how many HIPs they have, how many projects they have for the total number of people drawing in the company. We have no idea how many jobs they have running in parallel, whether the studio is three-headed or stacked. And of course, because we are IT specialists and we have twenty-five years of experience in running companies, we know how many and what kind of information systems a particular company needs, where the link to HR is, to the attendance system, what the link to accounting is, and so on.

The advantage is that we know and understand architectural practice, and today we have a number of architectural offices in our portfolio. That’s why architects don’t have to explain to us the elementary things they need in the software. For example, they do studies, documentation for zoning decisions and implementation documentation, because we simply know all this. We know what the typical size of their jobs are, how they should be structured, how many HIPs they have, how many projects they have for the total number of people drawing in the company. We have no idea how many jobs they have running in parallel, whether the studio is three-headed or stacked. And of course, because we are IT specialists and we have twenty-five years of experience in running companies, we know how many and what kind of information systems a particular company needs, where the link to HR is, to the attendance system, what the link to accounting is, and so on.

But it almost seems like architecture is a bigger love for you than graphic design…

I still enjoy building brands, of course, but I have to admit that theslight virtuality of graphic design is a hindrance. Architecture is good in that it’smore tangible, you meet the craft, the technology. I’m happy about the “weight” of the repair, the usefulness of repairing a few houses, and that it makes sense, because there are only a few functionalist villas here in Královův Polje that have not been destroyed. And of course, besides being a huge amount of fun, it’s become another pillar of our livelihood. It also helps that I don’t have to do architecture for someone else, I do it just for me and my friends, which makes the work a lot more efficient. It was quite evident, for example, on the Lidická street. There I was actually a co-investor, project manager, architect, and sometimes even construction manager in one person.

In your opinion, what is it that makes an architect able to imprint a building with an extraordinary spirit?

Humility! But then there’s another thing, and that’s true of any artwork, whether it’s graphic design or painting. Gombrich says in the very first chapter of The Story of Art that kitsch is what one does not doubt. What’s done just to please somebody. The architect who doubts is on the right track.